Ever thought of using pedagogical translanguaging in the language classroom? This comprehensive review navigates the effectiveness of translanguaging pedagogy for teachers.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: the emergence of pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING

- An educational approach to develop bilingual and multilingual learners?

- Can pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING in the classroom make a difference for language learning?

- Common goals of language learning in the contemporary context

- A study on the effectiveness of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy for the language classroom

- Benefit 1. Use of TRANSLANGUAGING support “Languaging” processes.

- Benefit 2. Using TRANSLANGUAGING activities enhance interaction and communication in the classrooms.

- Benefit 3. Engagement of TRANSLANGUAGING Practices enlarge space for linguistic experimentation.

- Benefit 4. TRANSLANGUAGING facilitates co-construction of knowledge.

- Benefit 5. Potential for incidental learning of additional languages beyond the target language.

- Benefit 6. Spontaneous TRANSLANGUAGING resembles the authentic experience of bilingualism and multilingualism in the society.

- Benefit 7. Potential to drive ideological shift in perception of target language.

- Drawback 1. Institutionalised TRANSLANGUAGING can lead to “Othering” effect.

- Drawback 2. Unfiltered TRANSLANGUAGING can be counter-productive for learning of minority languages.

- Drawback 3. TRANSLANGUAGING can cause under-engagement of the target language.

- Conclusion: Strengthening the TRANSLANGUAGING theory with a clear framework of pedagogical strategies.

- Recommended Readings

- References

Introduction: the emergence of pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING

Within bilingual and multilingual contexts, we have increasingly seen more scholars advocating for the use of “TRANSLANGUAGING” in education in the last decade. As language educators, we might be wondering: what is the effectiveness of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy in language classrooms?

When I started my career in language teaching, there was a lot of discussion on whether a first language (L1) can be used in a second language (L2) classroom. I was teaching Mandarin in the context of Singapore, where English language is dominant in society. While Mandarin is not exactly a “minority language” in Singapore, it is also not the most frequently used home language. Many of my students learn Mandarin as a L2 and use English as a L1. As such, it was not uncommon to see students using English spontaneously during Mandarin lessons.

I have to confess, despite undeclared policies and professional guidance from experienced colleagues, I chose to be more liberal in my approach: I did not enforce strict language separation and allowed more space in using languages other than Mandarin in my classroom. In fact, sometimes I might use it deliberately to provide better clarity in instructions and for the purpose of classroom management.

Notwithstanding that, I am extremely aware that many of my colleagues are strongly determined to adhere strictly to a monolingual approach, with the best intentions too. Their rationale is to maximise the use of the target language, Mandarin, especially when majority of the students are operating in a language environment with impoverished amount of Mandarin input.

As my knowledge of applied linguistics grew, I found myself reevaluating our core beliefs and methodologies pertaining to flexible language use in the classrooms. This process became particularly significant with the advent of TRANSLANGUAGING research, which provided a platform and a range of concepts for engaging in discussions about these topics.

Get real-time updates and BE PART OF THE CONVERSATIONS by joining our online communities on your favourite platforms! Connect with like-minded language educators and get inspired for your next language lesson.

An educational approach to develop bilingual and multilingual learners?

In my previous article on TRANSLANGUAGING, I gave an introduction to this concept which is generally deemed to have originated from a pedagogical approach in Wales. In that approach, students received input in one language and produce output in another (e.g. reading in English and writing in Welsh). Basically, this is an example of a pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING.

Beyond its origins, TRANSLANGUAGING has since been popularised and adopted by researchers and educators to extend to a wider variety of applications that can be pedagogical or social. It is recognised as the fluid language practices which are commonly used by bilinguals while challenging the traditional understanding of languages and bilingualism.

However, we also acknowledge the beliefs about language held by bilinguals and TRANSLANGUAGING scholars alike: named languages and the sociopolitical worlds these languages represent continue to shape the world as we understand it; they continue to provide the contexts in which we interact with other people.

“Bilingual education must develop bilingual students’ ability to use language according to the rules and regulations that have been socially constructed for that particular named language”.

García & Lin, 2017

Bilinguals have also been socialised to manage and perform within the general social expectations tied to named languages (e.g. ideologies of language separation). In other words, bilinguals learn to be monolinguals in each of their languages.

In response, bilinguals can use the TRANSLANGUAGING approach to carve out an additional space (the “Translanguaging Space”) to subvert such traditional understandings of language and culture, to express personal bilingual identities, and to engage with communicative experimentation.

Can pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING in the classroom make a difference for language learning?

This brings me back to my earlier days as a classroom language teacher. Can TRANSLANGUAGING have a place in the language classrooms? To put it simply, can TRANSLANGUAGING help learners learn a target language which is usually a named language? Yes, the target language that is defined sociopolitically and socioculturally, such as “English”, “Mandarin”, “Spanish”, “French”, “German”, “Japanese” or any language/variety with a name. For many language classrooms in K-12 educational contexts, the variety to be learned is in fact the academic version of the standard variety, and not the others which are mainly for general communicative use.

This brings us to the age-old debate whether a L1 (e.g. students’ home languages) can be used in a L2 (e.g. new language for the students) classroom. To be more specific and encompassing, it is really about whether languages/varieties other than the targeted one, can be used in the classroom. For example, with exaggeration and yet some truth, if you are teaching English in the UK, can Gaelic, Polish, Mandarin, Arabic, Hindi, Tyneside English, Singlish and all other languages/varieties one can name be used in the classroom?

Common goals of language learning in the contemporary context

How should we qualify “effectiveness”? How should we decide whether TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy can be considered to support language learning? My approach here is to consider measuring it against the common goals of language learning for the average language learner, parent and language teacher.

So, why would people be motivated to gain language proficiency or linguistic knowledge through formal education? Below are 4 possible reasons (non-exhaustive):

- To enhance employability in an increasingly globalised economic world, where one could gain a significant competitive edge by being capable of connecting and communicating with people from diverse backgrounds with the necessary language skills in their preferred languages;

- To acquire a deepened understanding of the cultures of specific speech communities that can be exemplified through the relevant language(s);

- To access content and knowledge in which a target language is used (we still basically listen and read a lot for many forms of knowledge acquisition); or

- To simply express personal identities through deeper engagement with a target language (e.g. student’s home language) that may be linked to personal heritage.

For the average language learner, parent, and language teacher, disrupting traditions of language education or subverting the conception of language as argued by TRANSLANGUAGING scholars would probably not be a priority (at least not a conscious one). To them, transformation through language education take other forms, such as the professional, economic and social opportunities gained after acquiring a second language.

Most of the time, effectiveness in such contexts is measured through success criteria such as whether the learners have attained their aspired results in standardised assessment; or whether learners have demonstrated evident gains in linguistic competence or performance; or if relevant stakeholders perceive the growth in the learners based on existing standardised measures.

Concurrently, as we strive to push boundaries in these contexts, such as the re-definition of success in language development or constructs of linguistic competence and performance, it would be useful for all stakeholders of language education to have some insights into the extent a pedagogy of TRANSLANGUAGING can have a role within current constraints.

Join our mailing list!

Receive insights and EXCLUSIVE resources on language education in a monthly newsletter, fresh into your inbox. No Fees, No Spam, so No Worries!

A study on the effectiveness of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy for the language classroom

Back in 2019, I did a systematic literature review of empirical studies to evaluate the effectiveness of translanguaging pedagogy in language education and presented at the “Inaugural Conference on Language Teaching and Learning: Cognition and Identity” held at the Education University of Hong Kong. My research question was fundamentally: “To what extent is TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy effective in facilitating language learning?”.

I did a scan of empirical studies conducted between 2014 and 2018 that could be related to TRANSLANGUAGING as exhaustively as I could go within the limitations I had. I excluded certain articles from analysis, such as those that were making theoretical arguments about TRANSLANGUAGING as a practical theory of language or about implementing TRANSLANGUAGING strategies for content learning. After the screening process, I placed 53 articles under my telescope.

Based on the coverage of these articles, majority were researching language classrooms based in North America and Europe, with only around 15 in Asia and Africa (diagram 1). There was a good spread of articles, generally between 10 and 14, across different levels of education (e.g. pre-school, primary, secondary, university, adult), though there were only 4 articles focusing on adult language education (diagram 2).

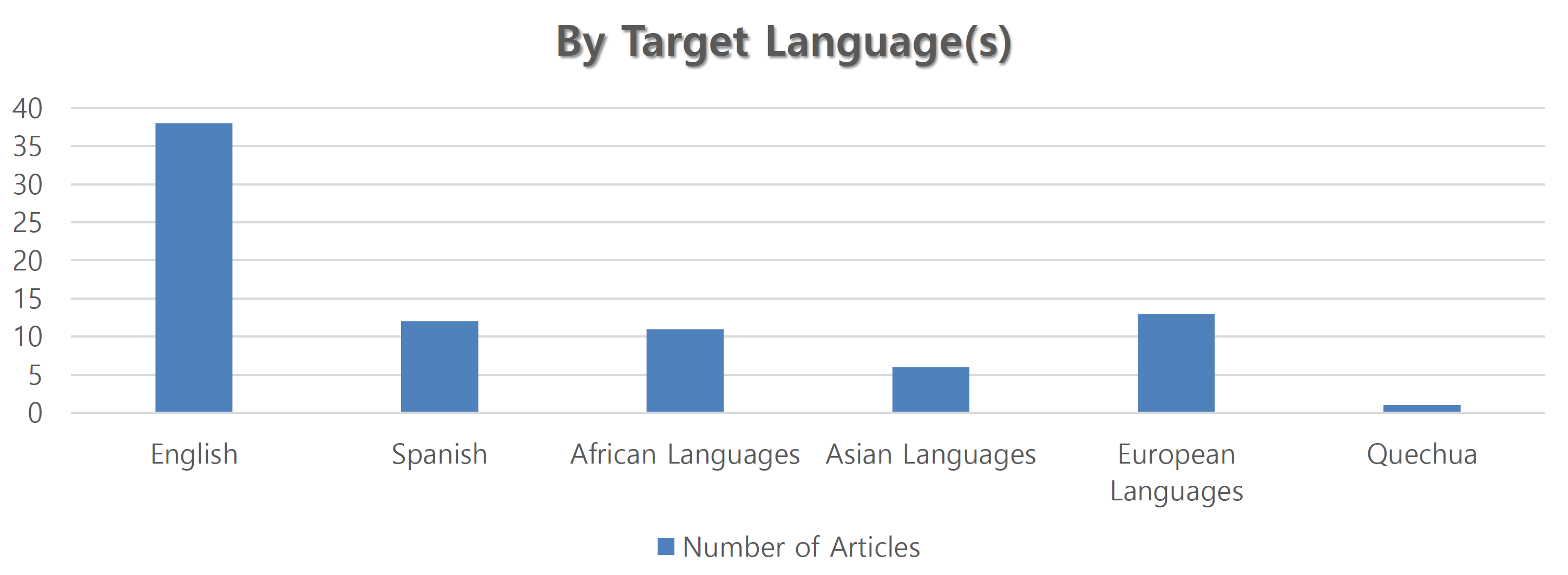

The main target language covered was English, unsurprisingly, though there was a good spread on Spanish, African languages and other European languages as part of the repertoire (diagram 3). On methodology, a sobering majority was based on qualitative research methods, with only less than 10 articles which used mainly a quantitative approach or a QUAN-QUAL mixed approach (diagram 4).

Benefit 1. Use of TRANSLANGUAGING support “Languaging” processes.

The review consolidated several benefits of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy as found by researchers, some which are more pronounced than the others. First and foremost, TRANSLANGUAGING supports “languaging” processes.

“Languaging” is a concept that has been pertinent in constructing the epistemological representation of translanguaging, and can be defined as the “process of making meaning and shaping knowledge and experience through language, part of which constitutes learning” (Swain, 2006).

Let me emphasise on the part of “process”, which essentially means doing things and performing meanings through language. The nature of TRANSLANGUAGING allows the languaging process to be more seamless, where learners are able to exercise total freedom and flexibility to construct meaning without directing attentional resources for language segregation.

Based on the studies reviewed, the subjects of “languaging” in our language classrooms can vary for different purposes:

- be about language itself, which thus leads to heightened metalinguistic awareness and multilingual awareness;

- be about thinking, thus stronger metacognition;

- be about culture and identity, and thus deepening knowledge about the target culture linked to the language or increased awareness of individuals’ cultural identities embedded within language; and

- be about any topic or content domain that the learners need to engage as vehicle for linguistic performance (e.g. to make better sense of sports and health to then do an oral presentation on the topic).

Benefit 2. Using TRANSLANGUAGING activities enhance interaction and communication in the classrooms.

The second benefit relates more to the affective side, where pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING can provide enhancements to the quality of interaction and communication. In a classroom where the target language is exclusively used, learners who have yet to achieve the requisite proficiency level (e.g. emergent bilinguals) may find it challenging to express themselves. Under such circumstances, these learners may choose to remain silent, thus losing out on opportunities of negotiation and clarification.

When linguistic barriers are removed, and learners are empowered with a larger repertoire of semiotic resources at their disposal, interaction and communication between different parties are enhanced (e.g. between learners which share common languages in dual language classrooms). Every learner is suddenly endowed with a voice which was traditionally blocked by linguistic barriers. This allowed them to express themselves flexibly and authentically.

TRANSLANGUAGING became a powerful enabler here as it minimised friction in the flow of thought and discussion that may arise from limitations in proficiency in the target language. We can also seize teachable moments to recast the conversations to model how it can be expressed in the target language.

Benefit 3. Engagement of TRANSLANGUAGING Practices enlarge space for linguistic experimentation.

One pertinent aspect of language learning is the process of linguistic experimentation, where learners attempt to apply what has been learned in their own novel ways. They may be testing their own hypotheses of the language forms and structures, or they could be finding their voice through the language which could well be a foreign language.

When learners perceive stronger empowerment through TRANSLANGUAGING, they can become more receptive of their personal cultural and bilingual identities. This can lower their affective filter, and enlarge the space for linguistic experimentation which involves creativity and risk-taking. These are qualities that have been traditionally understood to be correlated with higher efficiency in language learning.

Benefit 4. TRANSLANGUAGING facilitates co-construction of knowledge.

By fostering richer interactions and improved communication within the classroom setting through pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING, we create a more conducive environment for co-construction of knowledge amongst our learners.

For educators familiar with Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Framework of Learning and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD in short), learners have the capacity to attain skills and knowledge beyond their immediate level through meaningful socialisation, where different parties (e.g. teacher-facilitator and the learners) can build upon the sharing by one another to reach higher level of understandings. Again, such co-construction can lead to better metalinguistic awareness and multilingual awareness in the context of language classrooms.

Benefit 5. Potential for incidental learning of additional languages beyond the target language.

The benefits consolidated hitherto are the ones which different researchers have found repeatedly in different studies. Notwithstanding that, there are a few benefits that can be regarded as emerging, in the sense that they are not as commonly codified but are worth exploring further.

The first is the potential of incidental learning of linguistic knowledge of languages in the repertoire of all learners in a multilingual classroom – beyond that of the target language. For example, a Chinese learner could be learning linguistic concepts in Arabic in an “English as a Second Language” (ESL) classroom when engaging in TRANSLANGUAGING alongside other classsmates with Arabic as their L1. Over a sustained period, the Chinese learner may learn language and content in both ESL and Arabic (e.g. at elementary level).

Benefit 6. Spontaneous TRANSLANGUAGING resembles the authentic experience of bilingualism and multilingualism in the society.

The second emerging benefit is that TRANSLANGUAGING resembles the authentic experience of language use in bilingual/multilingual societies. In this sense, learners get to socialise and practise how they would use their language(s) in authentic scenarios. When they start to interact with other bilinguals and multilinguals in real life, there is less dissonance between a classroom experience and the real-life experience. This makes the experience of language acquisition more relevant than if the class adhered to a strictly monolingual policy.

We have earlier also stated that bilinguals and multilinguals have to adapt to the realities of society, where language use in many formal contexts tend to be strictly monolingual. Arguably, if learners get to experience both strict monolingual language use and bilingual/multilingual TRANSLANGUAGING through our pedagogical design, they are then socialised to the holistic realities of society. On the contrary, if the only experience in classrooms is strictly monolingual, learners may be less flexible to adapt to the different situations in society.

Benefit 7. Potential to drive ideological shift in perception of target language.

The last emerging benefit found was the possibility of ideological shifts in the perception of the target language. Where we uphold monolingual policies in our classrooms, we may impress upon our learners a representation of the target language which is tainted with various type of biases, including ideas such as strict formality and the lack of modernity.

TRANSLANGUAGING opens up new possibilities in the ways our learners use the target language, where the target language becomes part of their repertoire in constructing something creatively. When such ideological shifts happen, our learners can become more willing to learn the target language and engage in more “play with language”.

Get real-time updates and BE PART OF THE CONVERSATIONS by joining our online communities on your favourite platforms! Connect with like-minded language educators and get inspired for your next language lesson.

Drawback 1. Institutionalised TRANSLANGUAGING can lead to “Othering” effect.

Till this point, I hope that I have not built up an impression of a utopian language learning approach. Reality usually operates in grey areas and TRANSLANGUAGING is not the panacea for language learning (there probably is not one).

While most of the empirical studies reviewed presented a positive outlook and arguments in favour of TRANSLANGUAGING, there are some which illustrate the possible drawbacks. These are concerns of which language educators need to mindful should they want to adopt the pedagogy.

The first point is the “othering” effect of TRANSLANGUAGING in certain classrooms. Dependent on the student profiles within a specific class, this effect may come in different sizes. In classes where there is a sizeable group of learners having shared linguistic repertoires, a TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy offers them the opportunity to include or exclude selected students who do not share their home and school languages (e.g. minority language students).

This runs the danger of accentuating unequal power relations between our learners that we simply want to avoid in educational contexts. Certain learners may lose their voice in such situations, consequently causing an adverse impact on their educational outcomes.

Drawback 2. Unfiltered TRANSLANGUAGING can be counter-productive for learning of minority languages.

The second point is one which has been emphasised by Cenoz and Gorter in many of their articles, with “Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?” as the representative one. The main concern raised here is that TRANSLANGUAGING can become a threat for language classrooms where the target language is a minority language or any language which is not the dominant language in society (e.g. Arabic in a two-way dual language classroom in the US).

Studies which presented this concern demonstrated the trend where learners tend to switch to the majority language or insert features from the majority language in such classrooms. As such, where the intent of the language classroom was really to revitalise or maintain the use of the minority language, TRANSLANGUAGING becomes counter-productive as the majority language retains its power in communication and use.

Drawback 3. TRANSLANGUAGING can cause under-engagement of the target language.

The last point remains one of the strongest concerns with critics of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy, or critics of any language classroom which advocates the use of other languages beyond the target language. When pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING is not carefully planned out, it may be excessively used in replacement of the target language.

In a language classroom, especially that of languages with less presence in society, every minute of the curriculum time matters and modelling use of the target language is one very important function of language classrooms.

When the TRANSLANGUAGING space extends beyond the ideal threshold, it could potentially undermine the core objective of the language classroom, as it may result in reduced engagement with the target language. Unless there are good alternatives to provide language input in domains beyond the classrooms, teachers do have to calibrate the degree to which they use pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING.

Conclusion: Strengthening the TRANSLANGUAGING theory with a clear framework of pedagogical strategies.

So, is TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy viable in helping learners master a particular language? If indeed the intended outcomes of learning a target language are indeed as mentioned earlier, then we could at least argue that the pedagogical benefits that can be potentially reaped are strong enablers towards these outcomes. However, I do still have some lingering questions.

First, would research be able to demonstrate the effectiveness of TRANSLANGUAGING pedagogy in a more direct manner which is aligned with the common language learning goals? Such as observable gains in standardised assessment, or at least improvements in linguistic competence/performance? Of course, we can continue to debate on the constructs to be assessed or what we mean by “gains”, “competence” or “performance”.

However, with exception of a sporadic set of studies, such as the studies conducted by Mbirimi-Hungwe (2016) “Translanguaging as a strategy for group work: Summary writing as a measure for reading comprehension among university students” and Mgijima and Makalela (2016) “The Effects of Translanguaging on the Biliterate Inferencing Strategies of Fourth Grade Learners”, most studies demonstrate those benefits indirectly. Furthermore, where most of the studies have been designed with qualitative approaches, it is relatively unknown how some of TRANSLANGUAGING as pedagogy might perform at scale.

Second, majority of the studies reviewed were English-centric and euro-centric in nature. Beyond these regions, how would TRANSLANGUAGING fare vis-à-vis other approaches? Would other factors, such as language combinations implied within first and second language acquisition, come into interaction with the effects of TRANSLANGUAGING?

Last but not least, we have seen from majority of the studies which have tried to demonstrate when and how TRANSLANGUAGING works, while less studies surface the concerns that can be as important as the benefits. To me, a deepened understanding of what may not work in relation to what works is as important, as that would be the premise to shape the guidelines on pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING with clarity and nuancing.

That being said, my review project was completed in 2019, working on studies from 2014 – 2018. Would the last 5 – 6 years reveal further results beyond what I had concluded? I shall look forward to more discoveries ahead, and would definitely share here again when I have the updates. If you are also keen to try out pedagogical TRANSLANGUAGING, I will try to put together another article in future to share on the different actionable strategies that you can consider, even for parents! So, stay tuned with me on this website. Adios!

Thank you for reading! If you like what you are reading, do subscribe to our mailing list to receive updated resources and tips for language educators. Please also feel free to provide us any feedback or suggestions on content that you would like covered.

“Bilingual education must develop bilingual students’ ability to use language according to the rules and regulations that have been socially constructed for that particular named language”.

García & Lin, 2017

Recommended Readings

- Bonacina-Pugh, F., Da Costa Cabral, I., & Huang, J. (2021). Translanguaging in education. Language Teaching.

- Cenoz, J., and Gorter, D. (2017b). Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901-912.

- Cenoz, J., and Gorter, D. (2019). Multilingualism, Translanguaging, and Minority Languages in SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 130-135.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?. The Modern Language Journal, 94, 103 – 115.

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2015). Translanguaging and Identity in Educational Settings. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 20-35.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Chichester UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- García, O., and Lin, A.M.Y. (2017). Translanguaging in Bilingual Education. In García, O., Lin, A.M.Y., and May, S. (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education 3rd Edition (pp. 117 – 130). Cham Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Kieu, C.Y. (2019, June). Efficacy of Translanguaging as a Pedagogy in Language Learning Classrooms [Paper presentation]. Inaugural Conference on Language Teaching and Learning – Cognition and Identity, The Education University of Hong Kong.

- Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2013). 100 Bilingual Lessons: Distributing Two Languages in Classrooms. In Abello-Contesse, C., Chandler, P.M., López-Jiménez, M.D., & Chacón-Beltrán, R. (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education in the 21st Century: Building on Experience (pp. 107-135). Bristol UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Slembrouck, S., and Rosiers, K. (2018). Translanguaging: A Matter of Sociolinguistics, Pedagogics and Interaction?. In Avermaet, P. V., Slembrouck, S., Van Gorp, K., Sierens, S., and Maryns, K. (Eds.), The Multilingual Edge of Education (pp. 165 – 187). London UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wang, D. (2019). Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language Classrooms. Cham Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

References

Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Beres, A.M. (2015). An overview of translanguaging: 20 years of ‘giving voice to those who do not speak’. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 1(1), 103 – 118.

Bonacina-Pugh, F., Da Costa Cabral, I., & Huang, J. (2021). Translanguaging in education. Language Teaching.

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 401 – 417.

Cenoz, J., and Gorter, D. (2017b). Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901-912.

Cenoz, J., and Gorter, D. (2019). Multilingualism, Translanguaging, and Minority Languages in SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 130-135.

Cenoz, J. & Gorter, D. (2020). Pedagogical translanguaging: An introduction. System, 92. DOI: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102269.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?. The Modern Language Journal, 94, 103 – 115.

Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2015). Translanguaging and Identity in Educational Settings. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 20-35.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Chichester UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

García, O., & Kleifgen, J.A. (2019). Translanguaging and Literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 553-571.

García, O., and Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

García, O., and Lin, A.M.Y. (2017). Translanguaging in Bilingual Education. In García, O., Lin, A.M.Y., and May, S. (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education 3rd Edition (pp. 117 – 130). Cham Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG.

Hornberger, N., & Link, H. (2012). Translanguaging and transnational literacies in multilingual classrooms: A biliteracy lens. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 261 – 278.

Jaspers, J. (2018). The transformative limits of translanguaging. Language and Communication, 58, 1-10.

Kieu, C.Y. (2019, June). Efficacy of Translanguaging as a Pedagogy in Language Learning Classrooms [Paper presentation]. Inaugural Conference on Language Teaching and Learning – Cognition and Identity, The Education University of Hong Kong.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2012a). Translanguaging: Origins and Development from School to Street and Beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(7), 641-654.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2012b). Translanguaging: Developing Its Conceptualisation and Contextualisation. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(7), 655-670.

Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2013). 100 Bilingual Lessons: Distributing Two Languages in Classrooms. In Abello-Contesse, C., Chandler, P.M., López-Jiménez, M.D., & Chacón-Beltrán, R. (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education in the 21st Century: Building on Experience (pp. 107-135). Bristol UK: Multilingual Matters.

Li, W. (2011). Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222 – 1235.

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9 – 30

Li, W., & Lin, A.M.Y. (2019). Translanguaging classroom discourse: pushing limits, breaking boundaries. Classroom Discourse, 10(3-4), 209 – 215.

Lin, A.M.Y., Wu, Y., & Lemke, J.L. (2020). ‘It Takes a Village to Research a Village’: Conversations Between Angel Lin and Jay Lemke on Contemporary Issues in Translanguaging. In: Lau, S.M.C., & Van Viegen, S. (Eds.), Plurilingual Pedagogies: Critical and Creative Endeavors for Equitable Language in Education. Cham Switzerland: Springer.

Macswan, J. (2022). Codeswitching, Translanguaging and Bilingual Grammar. In McSwan, J. (Ed.), Multilingual Perspectives on Translanguaging. Bristol UK: Multilingual Matters.

Mbirimi-Hungwe, V. (2016). Translanguaging as a strategy for group work: Summary writing as a measure for reading comprehension among university students. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 34(3), 241-249.

Mgijima, V. D., & Makalela, L. (2016). The Effects of Translanguaging on the Bi Literate Inferencing Strategies of Fourth Grade Learners. Perspectives in Education, 34(3), 86-97.

Poza, L. (2017). Translanguaging: Definitions, Implications, and Further Needs in Burgeoning Inquiry. Berkeley Review of Education, 6(2), 101 – 128.

Sayer, P. (2013). Translanguaging, TexMex, and Bilingual Pedagogy: Emergent Bilinguals Learning through the Vernacular. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect, 47(1), 63-88.

Sembiante, S. (2016). Translanguaging and the multilingual turn: Epistemological reconceptualization in the fields of language and implications for reframing language in curriculum studies. Curriculum Inquiry, 46(1), 45-61.

Sembiante, S.F., & Tian, Z. (2020). The Need for Translanguaging in TESOL. In: Tian, Z., Aghai, L., Sayer, P., Schissel, J.L. (Eds.), Envisioning TESOL through a Translanguaging Lens. Cham Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Slembrouck, S., and Rosiers, K. (2018). Translanguaging: A Matter of Sociolinguistics, Pedagogics and Interaction?. In Avermaet, P. V., Slembrouck, S., Van Gorp, K., Sierens, S., and Maryns, K. (Eds.), The Multilingual Edge of Education (pp. 165 – 187). London UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Swain, M. (2006). Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced second language proficiency. In Byrnes, H. (Ed), Advanced Language Learning: The Contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 95–108). New York USA: Continuum.

Wang, D. (2019). Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language Classrooms. Cham Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Williams, C. (1994). Arfarniad O Ddulliau Dysgu Ac Addysgu Yng Nghyd-destun Addysg Uwchradd Ddwyieithog (PhD dissertation).